Prospectives From The Art World: The Crisis of Creativity

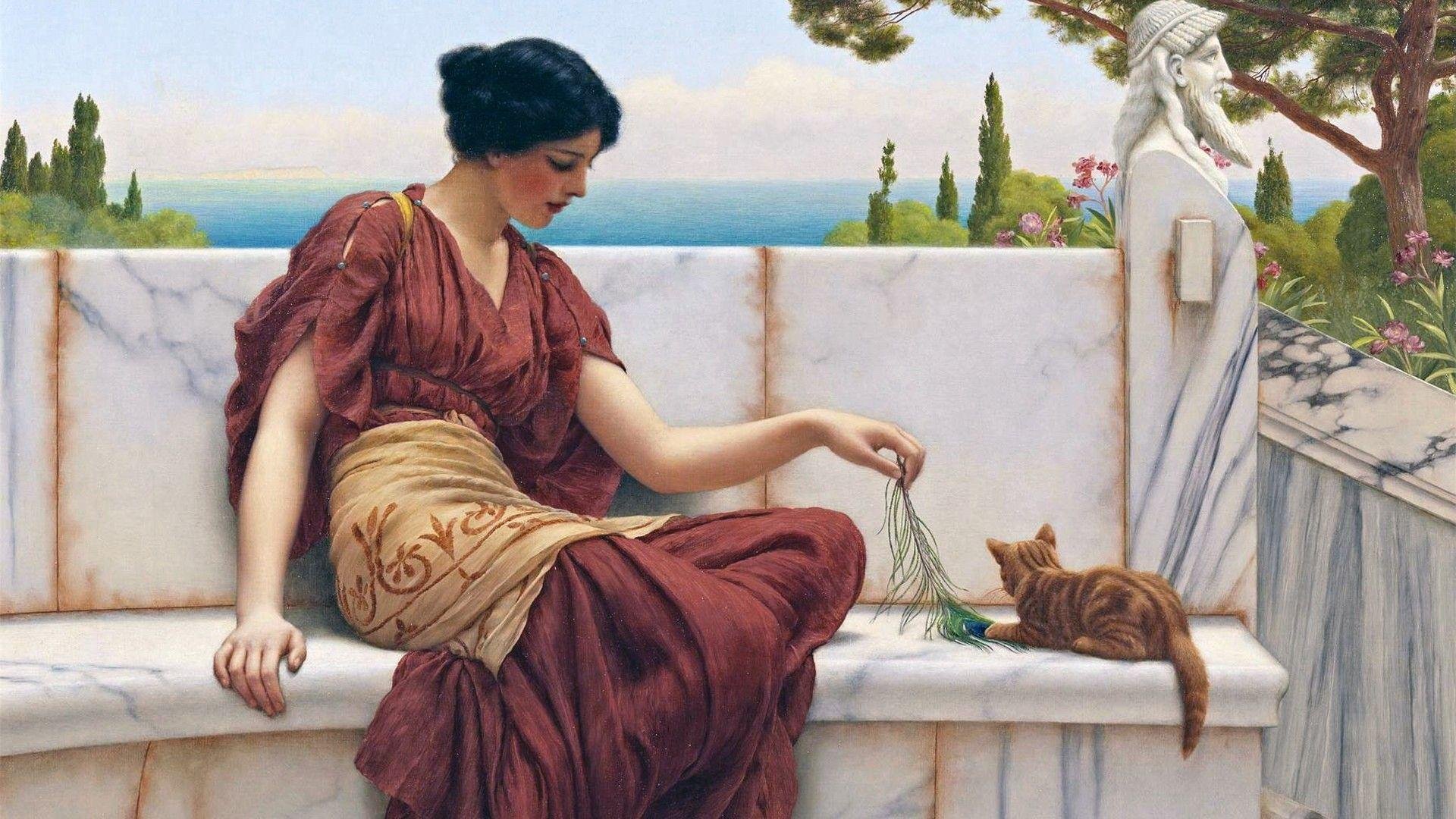

The Favourite, John William Godward, 1901

My brief stint in the various strains of the New York City art world included smoky underground galleries in batten warehouses in East Williamsburg, glossy white midtown parlors, and downtown dimly-lit gliztes with sparkles and champagne. Art, especially in times like these, has become a luxuriant decadence, a lazy afternoon opulence offered only to those who have the holy trifecta: funding, connections, and, most importantly, all the time in the world.

The art world is disillusioning because it is an illusion. The artist, the person with all the talent, is the least important part of the enterprise, especially if he is not old, dying, or dead. It's thrilling for an artist to make his first sale, say, for a measly thousand bucks—but not so thrilling when it goes up for auction for millions that the artist will never see. Artists, who tend to be nonstructural, bohemian free-spirits, are often maligned as financially illiterate hippies, anticapitalist subversives, vagrants and vagabonds, and fast-burning junkies who expire conveniently quickly and enrich the hedge funds that own all of the galleries, foundations, and auction houses long after they are dead. This was one crisis I had not anticipated.

The second crisis concerns what certain artists of certain backgrounds are "expected" or "allowed" to publish; if you are a minority of any kind, you can expect that you will only garner success if you make your identity the centerpiece of your creative underpinning, and especially if you primarily seek to commercially exploit the Suffering Of Your People. You are not allowed to present yourself as Artist first, [identity] second. You will always be [identity], [identity], [ethnic group], [income level] from [city] with roots in [country] or [religion], and if you are not creating art that stereotypically reflects one or all of these backgrounds—heaven forbid you are an aesthete or a classically-trained neo-baroque—you will be overlooked or dismissed without question. Not long ago, I attended a lecture in Harlem, where a Latin American artist was asked why he was "making pop art." Why did his art not look more "Indigenous?" Why did it look so "American?" These are also questions I have been asked about my work. Why does my writing sound so "classical?" Why do I not make more films about my "background?" Yes, why do I not remain within the confines of where I "belong?"

To dismiss this attitude as elitist belies the point, as artists have begun to internalize and perpetuate these ideals proudly. If I want to make it, they all seem to say, I had better start by portraying [my identity] as an impenetrable monolith, because we are a monolith, and we should all be creating art that is unremarkable and indistinguishable, one to the next.

Meanwhile, mediocrity is celebrated and sought after in the meme economy we have created and replicated. Artists are not artists, and people are not people. All are brands, all are branded, like cattle, fighting tooth and nail for fifteen seconds—you can forget about fifteen minutes—of blustering, whiplash-inducing [ir]relevance. It is more common that I see people taking selfies with art rather than looking at art. "I like this art," they are saying, "because it's part of my brand. It makes me look [better/smarter/more interesting]!" Art, at its core, is about human expression. It is about the artist expressing an emotion, and the viewer experiencing an emotion. Now, art lies at the core of the meme economy, where creativity is shunned in favor of popularity, of branding. Start with a base of some pre-existing, intellectual property: Disney characters, for example, how about Mickey Mouse? Make him "subversive" by drawing x's over his eyes, then make it "ironic" by adding a dollar sign somewhere. And, the piece de resistance? A Basquiat crown. After all, you're a real artist who appreciates real art, aren’t you? Yes? Then do not, under any circumstances, try to make something new.